| < Day Day Up > |

There are many different technologies available for providing memory capacity in a computer system. The primary memory (or main memory) of a computer system normally consists of silicon memory chips. This technology is typically two orders of magnitude more expensive per bit stored than magnetic storage technology, such as tapes or disks. Most computer systems also have secondary storage based on magnetic disks; the amount of such secondary storage often exceeds the amount of primary memory by at least two orders of magnitude.

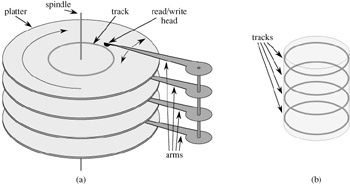

Figure 18.2(a) shows a typical disk drive. The drive consists of several platters, which rotate at a constant speed around a common spindle. The surface of each platter is covered with a magnetizable material. Each platter is read or written by a head at the end of an arm. The arms are physically attached, or "ganged" together,and they can move their heads toward or away from the spindle. When a given head is stationary, the surface that passes underneath it is called a track. The read/write heads are vertically aligned at all times, and therefore the set of tracks underneath them are accessed simultaneously. Figure 18.2(b) shows such a set of tracks, which is known as a cylinder.

Although disks are cheaper and have higher capacity than main memory, they are much, much slower because they have moving parts. There are two components to the mechanical motion: platter rotation and arm movement. As of this writing, commodity disks rotate at speeds of 5400-15,000 revolutions per minute (RPM), with 7200 RPM being the most common. Although 7200 RPM may seem fast, one rotation takes 8.33 milliseconds, which is almost 5 orders of magnitude longer than the 100 nanosecond access times commonly found for silicon memory. In other words, if we have to wait a full rotation for a particular item to come under the read/write head, we could access main memory almost 100,000 times during that span! On average we have to wait for only half a rotation, but still, the difference in access times for silicon memory vs. disks is enormous. Moving the arms also takes some time. As of this writing, average access times for commodity disks are in the range of 3 to 9 milliseconds.

In order to amortize the time spent waiting for mechanical movements, disks access not just one item but several at a time. Information is divided into a number of equal-sized pages of bits that appear consecutively within cylinders, and each disk read or write is of one or more entire pages. For a typical disk, a page might be 211 to 214 bytes in length. Once the read/write head is positioned correctly and the disk has rotated to the beginning of the desired page, reading or writing a magnetic disk is entirely electronic (aside from the rotation of the disk), and large amounts of data can be read or written quickly.

Often, it takes more time to access a page of information and read it from a disk than it takes for the computer to examine all the information read. For this reason, in this chapter we shall look separately at the two principal components of the running time:

the number of disk accesses, and

the CPU (computing) time.

The number of disk accesses is measured in terms of the number of pages of information that need to be read from or written to the disk. We note that disk access time is not constant-it depends on the distance between the current track and the desired track and also on the initial rotational state of the disk. We shall nonetheless use the number of pages read or written as a first-order approximation of the total time spent accessing the disk.

In a typical B-tree application, the amount of data handled is so large that all the data do not fit into main memory at once. The B-tree algorithms copy selected pages from disk into main memory as needed and write back onto disk the pages that have changed. B-tree algorithms are designed so that only a constant number of pages are in main memory at any time; thus, the size of main memory does not limit the size of B-trees that can be handled.

We model disk operations in our pseudocode as follows. Let x be a pointer to an object. If the object is currently in the computer's main memory, then we can refer to the fields of the object as usual: key[x], for example. If the object referred to by x resides on disk, however, then we must perform the operation DISK-READ(x) to read object x into main memory before we can refer to its fields. (We assume that if x is already in main memory, then DISK-READ(x) requires no disk accesses; it is a "no-op.") Similarly, the operation DISK-WRITE(x) is used to save any changes that have been made to the fields of object x. That is, the typical pattern for working with an object is as follows:

x ← a pointer to some object

DISK-READ(x)

operations that access and/or modify the fields of x

DISK-WRITE(x) ▹ Omitted if no fields of x were changed.

other operations that access but do not modify fields of x

The system can keep only a limited number of pages in main memory at any one time. We shall assume that pages no longer in use are flushed from main memory by the system; our B-tree algorithms will ignore this issue.

Since in most systems the running time of a B-tree algorithm is determined mainly by the number of DISK-READ and DISK-WRITE operations it performs, it is sensible to use these operations efficiently by having them read or write as much information as possible. Thus, a B-tree node is usually as large as a whole disk page. The number of children a B-tree node can have is therefore limited by the size of a disk page.

For a large B-tree stored on a disk, branching factors between 50 and 2000 are often used, depending on the size of a key relative to the size of a page. A large branching factor dramatically reduces both the height of the tree and the number of disk accesses required to find any key. Figure 18.3 shows a B-tree with a branching factor of 1001 and height 2 that can store over one billion keys; nevertheless, since the root node can be kept permanently in main memory, only two disk accesses at most are required to find any key in this tree!

| < Day Day Up > |